That's right. The headline was entirely mine! You're welcome.

BTW, I'm releasing a new book I co-authored with Ralph Nader about the forklift industry. Unsafe at any speed II.

Forklifts Hurt Thousands of Workers Each Year. Factories Are Seeking Alternatives.

The vehicles are involved in nearly 100 deaths each year; companies say demand growing for autonomous versions

By John Keilman, WSJ

Jan. 5, 2025 5:30 am ET

Whirlpool’s washing-machine factory in Clyde, Ohio, has eliminated forklifts from its production area.

Some of America’s biggest manufacturers are backing away from forklifts.

The vehicles have been integral to factories and warehouses for more than a century, but now companies are aspiring to go “forklift-free” to improve productivity and safety. Federal statistics show that each year around 7,500 workers are injured in forklift-related collisions, tip-overs and other mishaps, while nearly 100 are killed.

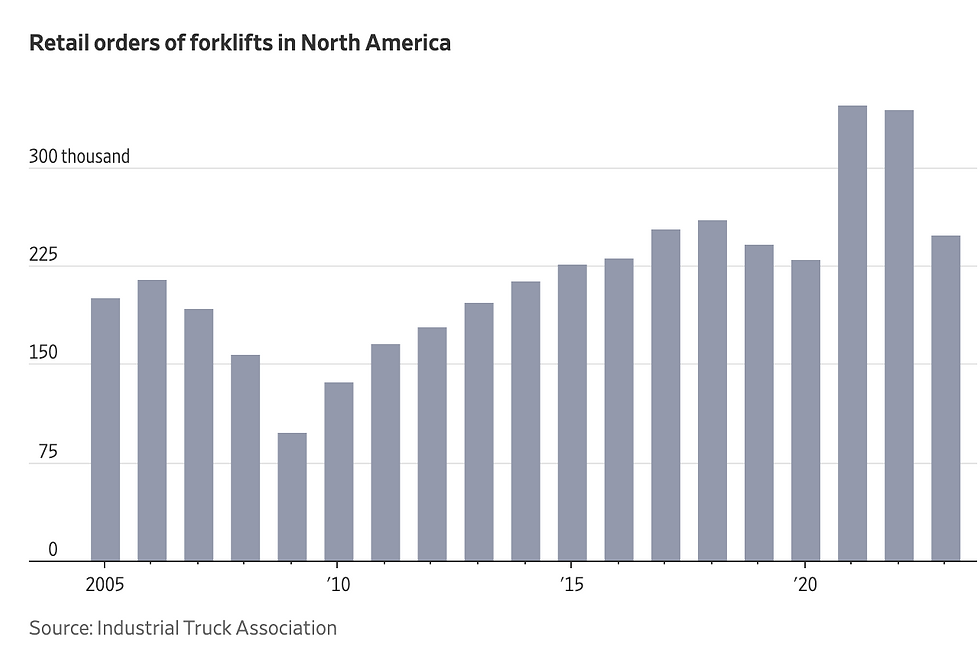

Retail orders for forklifts dropped 28% in 2023, the biggest annual decline in 14 years. Industry participants described the decline as a normalization of sales following the pandemic’s warehouse construction boom.

Plastic-pipe manufacturer Ipex designed its new factory in North Carolina to minimize the use of forklifts, relying instead on overhead cranes and hand-pushed electric pallet jacks. That made the plant, which opened in 2023, a safer, quieter and less stressful workplace, said Johnny Drummond, the company’s director of manufacturing.

Ipex designed its new factory to rely on overhead cranes and hand-pushed electric pallet jacks.

“Employees feel like they can walk anywhere within the interior shop floor and not have to look out for forklifts,” Drummond said.

Mercedes-Benz has been trying to reduce forklifts in its U.S. plants since 2018, replacing some with autonomous vehicles. Tesla is making a similar effort, using push carts and trailer-hauling “tuggers” inside its factories to cut down on traffic and injuries, a person familiar with the matter said.

Manufacturing safety consultant Larry Pearlman said that few clients a decade ago were looking for substitutes for forklifts, also known as lift trucks. Today roughly 10% are, and he expects that portion to grow as robotic material carriers become more widespread.

“The occasional lift truck might be kept in the spare room or something, but definitely, if I’m a futurist, I see it going away,” said Pearlman, founder of Safety and Consulting Associates.

Well-known risks

Forklift manufacturer Clark takes credit for inventing the vehicles in the early 20th century, and in the decades that followed, they became a factory staple. Forklifts can carry loads that weigh thousands of pounds and lift pallets high onto warehouse shelves, allowing workers to move large amounts of material quickly.

The vehicles come with well-known risks. Documents from state and federal regulators detail the deaths of workers in forklift-related incidents, including three that happened in 2023 over the span of 21 days.

One worker was killed when he was struck by a forklift driver whose view was obstructed by the totes the vehicle carried. Another operator plunged to his death when his forklift fell from the truck he was loading. A third died when he was crushed by a forklift’s lifting mechanism in an incident a police investigator labeled “horseplay.”

Injuries can be severe. Former warehouse worker Adelaida Anderson sued forklift manufacturer Raymond after she said she fell from one of the company’s stand-up models when it hit a crack in the floor. The forklift’s steer wheel crushed Anderson’s left leg, which had to be amputated below the knee.

Anderson claimed the forklift was defective because it didn’t have a door that would have kept her from being ejected. Raymond said federal standards mandate open compartments so operators can escape during an emergency.

After years of litigation, a federal jury in 2024 awarded Anderson $13 million. Raymond, which declined to comment, is appealing the judgment.

Forklift makers say they have added numerous safety features to their vehicles. These include high-visibility seat belts that make it easy to see whether an operator is wearing it, lighting that warns pedestrians a forklift is coming and sensors that slow the vehicle before a collision takes place.

Manufacturers also preach adherence to training rules. Federal regulations require workers to undergo instruction before they can operate a forklift, and to be re-evaluated every three years. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration issues roughly 2,000 citations a year to companies whose training programs are deemed inadequate.

Forklift manufacturers say there is high turnover among drivers and lament what they call the glorification of unsafe operation. Dozens of TikTok and YouTube accounts feature videos showing drivers skidding, crashing and dropping oversize loads that smash across warehouse floors.

A robotic future

Brian Feehan, president of the Industrial Truck Association, a trade group for forklift makers, said that despite the postpandemic sales drop, he doesn’t expect “a big diminishment” in the business. Some companies that make the vehicles say demand is shifting as customers seek autonomous versions.

Whirlpool’s washing-machine factory in Clyde, Ohio, has eliminated forklifts from its production area, and uses robotic tuggers to deliver parts to assembly-line workers. Other company plants are following suit, said Kristin Day, Whirlpool’s vice president of U.S. manufacturing operations.

She said the tuggers have reduced injuries and near misses in the factories. They also have improved efficiency by delivering “right-sized” loads of parts that don’t need to be portioned into smaller containers.

Brett Wood, chief executive of Toyota Material Handling North America, a branch of the world’s biggest forklift maker, said the industry could see transformational changes in the next five to 10 years, particularly if boxes replace pallets as the preferred storage platform.

“I can picture an order picker someday without a person on it, and it’s got an arm and it’s going up and it’s picking a box automatically and coming down with it,” he said.

Hyster-Yale Materials Handling, which makes forklifts under the Hyster and Yale brands, has replaced some of the vehicles with autonomous tuggers in its own factories, a move it considers an upgrade. But CEO Tony Salgado said not every manufacturer is ready or able to make such a switch.

“For the foreseeable future, manual lift trucks will be in high demand,” he said.

For now, even companies aspiring to forklift-free status still rely on the vehicles. Whirlpool uses them in parts of its Clyde factory where large, bulky items are transported. Older plants run by Ipex, the pipe maker, have floor layouts and production procedures for which forklifts are necessary.

“It’s kind of a big challenge to eliminate them,” Drummond said. “We take it one bite at a time.”

Becky Peterson contributed to this article.

Comments